I hung up the zoom call with my producer and felt my soul crush as it hit me that the Deniliquin Ute Muster was just a week away. I still hadn’t heard Project Cactus run, much less drive under its own power, and I understood that getting a vehicle running and driving was just the starting point for a series of lengthy troubleshooting jobs needed to create a roadworthy chariot. I had to fire up that Australia-engineered “Hemi-Six” engine — like, right now. [ED NOTE: This is Matt here to remind you that it takes a lot of resources to make stories like this happen. Please consider becoming a member of The Autopian to support more projects like this. Emphasis on the “like,” because this was crazy. David’s spent the last week trying to blast out this story, including all of Christmas Eve. – MH]

I was amazed at how far Laurence and I had come after just four weeks “on the spanners” (as he’d put it). We’d turned the ute you see above into something somewhat resembling a vehicle; there were now doors, there was a windshield, there was an engine hooked to a transmission, there was a radiator, and there were bits of an electrical system. Plus, the neighbor, legendary hotrod builder Hud Johnston, had welded up all the rust holes with patches that we then ground down and cleaned up via liberal application of black, goopy bedliner. The vehicle appeared to be almost all there, but whether that’d be enough to get it over 400 miles from Dubbo, New South Wales to Deniliquin in six days was anyone’s guess. We still had a broken steering column, a missing fender, no face, numerous electrical faults, and a motor we had yet to hear run. Despite all our progress, to the layperson, the car still looked like a wreck:

Laurence and I did, too, as we’d each spent over 18 straight hours working on this stubborn ute — it was the longest wrenchfest of either of our lives, and it showed on our faces:

But the next day taught me something that I’d like to communicate to fellow downtrodden wrenchers: Remember that tomorrow is a new day. I realize that’s a cliche expression, but the Friday that we were supposed to have completed our inspection — day one of a three-day block of time we had before our next inspection deadline — made it clear just how much fatigue had played into that feeling of hopelessness and futility. Laurence and I woke up, saw the faceless ute, and — now well-rested — devised a plan that had us both feeling moderately hopeful. The dust had settled from our explosive wrenchathon, and it appeared that most of the hard work was actually complete; we had an engine, transmission, drivetrain and a solid body, and we still had Friday, Saturday, and Sunday before inspection, plus Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday before we were supposed to depart for Deni. Despite what our weary selves had thought Thursday night, putting a plan together after a solid night of sleep had us both feeling invigorated. Now it was time to execute.

Six Days Until The Deni Ute Muster

Fixing The Steering Column

My biggest concern was the steering column, whose shift lever Laurence had brilliantly tried to muscle into submission when the transmission refused to go into gear. The result was an unfixable piece of shattered aluminum in the column:

“She’ll be right,” Laurence refrained (along with the requisite “no worries” that echoes throughout the whole of Australia) seemingly every minute of every day since I’d arrived. “How can this man be so confident? Is he a bit delusional?” I sometimes wondered early in the trip. “Look at this machine! What about this thing can one possibly say will be ‘right’?” But after a few days hanging out with Laurence, we quickly became friends, and I realized that he’s far from delusional — in fact, I’d call him almost entirely “lusional” if that were an actual word. I noticed that, when it came to fixing Project Cactus, Laurence backed up all of his assurances with results. How? Well, the answer is that Laurence is one of the world’s foremost experts on Chrysler Valiant utes, and that’s not an exaggeration in the slightest. The number of people who know more about Australian Chrysler Valiants — about their history, about their mechanical makeup, about their value on the marketplace — than Laurence is maybe in the double digits. Maybe. Laurence’s experiences with his old Chrysler Valiant wagon, and with his beautiful Charger, made such an impression on him that it led him to read all the books about these machines, it led him to join all the internet forums, and it led him to get in touch with all the local Valiant owners — Laurence is in deep in the Chrysler Valiant world, and you need only look in his childhood home to see how deep. Here’s Laurence pulling multiple steering columns from his shelf. This broken part that had me so worried — Laurence had multiple replacements right there in his mom’s shed!:

Plus, there were tons of other parts; there’s a radiator to the right of him on the ground in this photo, plus a bunch of heater boxes on the shelf, along with a valve cover:

Need a spare flywheel? Here’s one of probably at least a handful he has sitting around:

Laurence has an entire three-speed manual transmission just sitting on cement bags, and is that an axle shaft standing up?:

I should have known that Laurence was the Valiant-whisperer, for one of our very first interactions involved him mailing me — all the way from Australia to Detroit — this “Another Valiant Still Going Strong” sticker for my 1965 Plymouth (not Chrysler, as they were branded in Oz) Valiant:

Anyway, with multiple new steering columns in hand, we headed back to the shed, where we were met with the hotrodding legend, Hud, as well as Laurence’s brother Mitch and fabricating magicians Callum and Henry.

You can see Mitch working on installing the windshield washer bottle, while Henry and I are in the cabin trying to dismantle the broken steering column, since I didn’t feel like unbolting the whole thing from the steering box and replacing it with an entire new column. Here I am holding the replacement bit that I extracted from one of Laurence’s spares:

Here I am trying to yank a part of the broken column by using the steering wheel as a puller. It did not work:

Here’s Henry doing things the right way:

Henry and his friend Callum are two of the most positive people I’ve ever met; they’re a true joy to be around. The two have been buddies forever, and now run Iron Knuckles Fabrication, a shop that conducts ridiculously high-end custom car jobs:

The fact that these two craftsmen — these artists — took time out of their day to drink beer and help me repair a shitbox is a testament to the depth of car culture in this part of Australia. It’s not about showing off your fancy car or your skills, it’s about forging relationships with people who get you. (It’s also about the beer, to be sure).

To replace the broken part of the column, I had to cut the connector off at the bottom, then pull the turn signal switch you see dangling in the image above all the way out:

Installing the new column bit wasn’t difficult; it required a set of snap-ring pliers, a flathead screwdriver, and a hammer, but none of this was challenging:

Having to shove all those wires from the switch back through the bottom of the column was borderline impossible, so I just shoved them through the top, and later bundled them and ziptied them to the column; here are all the wires I had to deal with (I’d also like to point out in the photo below that Laurence and I modified an automatic brake pedal cover to fit over our smaller manual brake pedal using a saw and some black silicone):

With the replacement part in place, and the column reassembled, I grabbed the shift lever, wiggled it around a bit, and gave Henry a high-five — one of my biggest concerns had been eliminated thanks to Laurence’s hoarding and some help from this kind, bearded fabricating genius. Still, my deepest worry remained, and that was the engine — though we’d compression checked it and oil pressure tested it, we still hadn’t heard it run, and as I said before — getting it running was just the first step in a long list of operations, and time was running out quickly.

Will It Run?

After hooking up as much of our wiring as he could, Laurence’s brother Mitch shot some “Start Ya Bastard” starting fluid into the the engine’s (and I’d like to reiterate that this was engine number four, after the first three ended up totally kaput) carburetor, and I wiggled the key in the ignition switch. To my surprise, the motor turned over! Somehow the wiring from that switch, which had all been exposed to the elements for years, wasn’t all completely destroyed. The engine didn’t fire, though. I held a jumper-wire between the battery and distributor (which I had just plopped onto the engine so that the timing was at least somewhat close; I did not tune it), and Callum jiggled the key: Still just a crank.

To test for spark, I shoved a sparkplug into one of the wires, and held the base of the plug against an engine bracket; I saw no spark while the engine cranked, indicating we had some kind of electrical fault somewhere.

I adjusted the points, we checked all of our connections, and then Henry taught me his “paint can method” for metering small quantities of fuel into an engine: You just pour the gas into a paint can lid, and allow the fuel to drip out of the tiny vent hole:

I jiggled the keys, and the engine ROARED to life, before shutting off with a big fireball from the top of the carburetor:

Not ideal, but the engine did run, and that was a humongous relief. Getting it to idle without shooting flames would be a problem for future-me.

Five Days Until The Deni Ute Muster

The next morning, Laurence and I spent far too much time at the hardware store deliberating which type of sheetmetal to buy to cover the sharp inner door skins. We decided to go with “Gal,” which it turns out has nothing to do with Wonder Woman, and everything to do with protective zinc coating on steel.

Getting The Engine To, You Know, Not Shoot Flames

A post shared by The Autopian (@theautopian) Laurence and I had done absolutely no tuning to either the carburetor or distributor; we hadn’t even rebuilt the carb. The thing had been sitting on a shelf for years, and we’d bolted it to a rusty intake manifold that had been fastened to an engine buried in a chicken shed. The fact that Cactus’s motor ran at all was a miracle. What was even more miraculous was what happened when we cranked the distributor a few degrees; the backfiring stopped, the flames went away, and the mighty Hemi Six idled! Listen to that motor purr in the video above, as it sips gasoline out of a jerry can. Later that night, Laurence hooked the carburetor to the fuel pump, which was hooked to the fuel tank. Then we filled the tank with gas, and were pleased to observe no leaks:

The big-diameter rubber hose we needed to span from the filler neck to the tank is something we ended up snagging from town — particularly from Stevenson’s Hydraulics, a shop that specializes in hoses and fittings. This store, shown below, is one of many outfits in Dubbo — a town whose primary industries are farming and mining — that made Project Cactus even remotely possible. Trade-based towns, particularly farm towns, are where car culture flourishes, in part because tradespeople are handy, and also in part because the industry supporting such trades tends to also be an industry that supports building things.

While out, Laurence introduced me to the fabled “Chiko roll,” which — while delicious (despite the motor oil from my hands) — is the most confusing, vegetable-y, non-eggroll I’ve ever eaten. I have absolutely no idea what’s in one, and reading the Wikipedia page does nothing but infuriate me. Get a load of this: What the hell, right?

Anyway, on the table in front of me is a delicious bottle of flavored milk, and more importantly a special copy of the Photo News, Dubbo’s premier newspaper. As a journalist, I’m a huge fan of local newspapers for a variety of important social reasons that I don’t have time to get into, but for now, I’ll tell you I’m a huge fan because journalist John Ryan, a car-nut and fellow Chrysler Valiant owner, wrote this:

A post shared by David Tracy (@davidntracy) Moving on from those asides about farm stores in Dubbo, Chiko rolls, and the local newspaper, here’s a look at what the engine sounded like once we’d gotten it running from Cactus’s gas tank:

Listen to that smooth idle — and all from a carburetor that hadn’t been rebuilt or tuned, from a distributor that we hadn’t adjusted with a timing light, from an intake manifold out of a chicken shed, and on and on. This was incredible!

Adjusting The Shifter Linkage Without Breaking It

In an attempt to avoid breaking our column again, we referenced Laurence’s ute, shown above, to adjust our shifter linkage. The way a column shift works is, pulling the lever behind the steering wheel moves a fork under the hood; that fork swings those two arms in the image above. Attached to the end of each arm is a rod, which reaches down to the gearbox, shifting gears:

You can see how the end of the shift rods threads into a little block that slots into a bracket, which is bolted to the gearbox. To change the length of each rod requires threading that block, but my rods and blocks were totally coated in grime:

Adjusting these rods was impossible, and I feared I was going to shear them if I kept trying. Not a worry, though, because Laurence just dipped the rods into his ultrasonic cleaner (which he’s mighty proud of), and waited a few hours; they came out looking almost brand new:

Basically, what this cleaner does is send high-frequency sound waves through a cleaning fluid (in this case Evapo-Rust), leading to cavitation, which basically eats away at the surface of whatever part you’ve got in the bath. It made adjusting the linkage easy; once we installed the rods back onto the vehicle, the shift lever on the column worked like a charm:

Laurence and I put the linkage, as well as the transmission and entire drivetrain, through a first test by raising the car on the hoist, firing up the engine, and rowing through the gears:

The ute cruised through all gears — one through three, then reverse — flawlessly.

Installing Project Cactus’s New Face

Laurence, the hoarde — I mean passionate Valiant owner — he is, had a spare fender, which was great luck, because somehow the one body panel that Project Cactus had when Laurence had purchased it as a parts ute was the wrong fender, which would not facilitate our headlight or grille. Laurence patched the small rust hole at the base of the brown replacement fender using metal (and by metal, I actually mean “silicone,” but don’t tell anyone), and then bolted it up to the body:

With the fender on, Project Cactus could finally have a face! Now it had black, white, brown, and blue body panels, and frankly, was starting to look like the “feral ute” that a wild drunken car show like the Deni Ute Muster deserves.

On Saturday night, the vibes around the shop were good! We had a running and idling motor, we had a column-shifter and drivetrain that worked, we had every body panel except the hood — we were close to having something ready for a test drive.

I went to sleep in good spirits, even after realizing that I had permanently stained almost every clothing item I’d brought to Australia.

Three Days Until The Deni Ute Muster

Doing Some Work On The Interior

Sunday, the day before inspection, was mostly a fun day, minus the absurd electrical gremlins we had to locate and then tackle. Two of Hud’s friends came over and helped us get much of our lighting sorted, while I measured the doors and then cut up the galvanized steel we’d bought from the store. Here’s what the door looked like before:

And here it is with my new panel in place:

It’s not going to win any awards, but it should get us through inspection, I figured.

The seat was also in desperate need of attention, as you can see above. To at least get the thing looking remotely presentable, I folded and then shoved that foam roll you see in the image above into the giant crater in the seat, tightened it down with duct tape, and then installed that seat cover in the bag shown above. Here’s the result:

After fixing some grounding issues, Laurence got the steering wheel installed and the horn working; he then found a small hole in the floor, which he fixed — again — with “metal”:

Look, none of this stuff was meant to resemble anything approximating “good,” it was just meant to get close to “acceptable.” That’s all. Whether we’d manage it would be up to the town’s most lenient safety inspector, whom Laurence had done quite a bit of research to track down; more on that later.

The Maiden Voyage

Too excited to bolt in the now-covered bench seat, or the hood, I chucked a spare tire into Project Cactus’s cabin, and Laurence and Bek watched on as I jiggled the key and fired up the mighty Hemi-Six. The motor roared and idled at way too high of an engine speed, but I didn’t care. I let off the clutch to drive forward; the engine immediately shut off. Again, I didn’t care. I needed to drive this machine in order to discover other problems that would be revealed by the engine speed eclipsing 3,000 RPM, the transmission shifting, the driveline spinning at high angular velocities, the suspension rolling over bumps at speeds, the brakes trying to bring the car down from 30 mph. If I waited until moments before the inspection to get my first drive in, I’d risk finding a problem too late.

So I fired the engine back up, revved it even higher than before, and feathered the clutch to keep the engine’s loads down so it wouldn’t stall. The ute lurched forward, shooting mud up from Laurence’s yard. I stayed in it and headed down the driveway:

As you can see, we only had one functioning taillight, and Laurence noted how obvious it was that our exhaust (which we’d pieced together from scraps in a field) was sitting very, very low to the ground:

In case you’re curious, that exhaust is only held up at the engine on one end, and at the rear bumper on the other:

Still, the muffler was doing its job, as the car was mostly quiet aside from the high-revving engine completely exposed due to a lack of hood:

I continued driving down Laurence’s driveway, shifting through the gears and testing the brakes:

His driveway is long, you see, and very much not a public road, for driving down a public road with a vehicle in this shape would be inadvisable.

With a single headlight on one side and a turn signal bulb on the other lighting the roa—I mean, driveway— ahead, I matted the gas pedal and let the smooth motor belt a lovely tune into the darkness. I let off, pressed the clutch, and my left hand yanked the shift lever up, forward, and up into second. I pressed the gas again as I let off the clutch, and the car stuttered and lurched, only to then accelerate with fury down this dirt path. I then pulled that shifter down into third, and — again, after a bit of a lurch — the vehicle sped up, its suspension handling the bumps with alacrity, the steering feeling reasonably tight, the brakes slowing everything down controllably, and the driveline much, much quieter than I expected. Honestly, everything was quiet aside from that screaming motor that kept stuttering.

The cooling system seemed to hold (I had no gauge to look at, but I could see the top of the radiator, and there was no geyser in sight), that transmission shifted perfectly, and the pitted rear differential didn’t make even a tiny whine. I stepped out to hang out with Laurence, his friend Ben, and Ben’s wife Brittany, who had driven by to see the spectacle. We stood there ogling the running ute for what felt like an hour. Its motor was humming. It was driving. And it was doing so far, far better than any of us could have expected.

As I walked back to Cactus to drive back to Laurence’s garage, I heard a hissing sound — one that I was all too familiar with. “Hmm. That’s a vacuum leak” I said out loud. I stepped closer to the motor, shined my light on the back of the carburetor, and saw that there was a huge vacuum port wide open. Laurence and I had somehow missed it, and as a result, the engine was trying to send the right amount of fuel to go with the air coming in through the carburetor’s throttle, but the fuel volume was way off since it wasn’t accounting for all the air leaking in through the port at the back of the carburetor. I hopped into the Valiant, stole the plastic threaded piece at the top of the door that goes over the lock, and shoved it into the open port, sealing the leak. The engine immediately went from 2,000 RPM to a beautiful, whisper-quiet 800 RPM idle. I mean this when I say it: The idle was perfect. How was this even possible? We’d just chucked the carburetor on there without doing anything to it! We’d just cranked the distributor by hand without using a timing light to get the spark timing right! This engine was one we hadn’t even heard run, it had only 70 PSI of compression on cylinder one during our testing, and that intake and exhaust manifold had been buried in a chicken shed. But none of this mattered; Project Cactus truly idled perfectly.

But that pales in comparison to what I felt when I hopped back onto that wheel I was using as a seat. When I let off the clutch, the car no longer lurched; it smoothly flowed forward, and accelerated with vigor. Each gear-change from that three-speed transmission Laurence had purchased from his friend along with a rusted, stuck engine was smooth as silk, with absolutely no grinding or lurching. The ute felt powerful, it felt smooth, and it felt like it not only wanted to drive to Deni, but to the ends of the earth. It was the most impressive first drive I’ve ever experienced in a project car. The vehicle that had started out as a rusty pile of metal had beaten Laurence and me up for four weeks; it had pushed us to our limits, but finally, for the very first time, it showed mercy, and gave up its desire to die. Project Cactus was now very much alive and motivated to thrive.

Inspection Day: Three Days Before The Deni Ute Muster

We got up early on Monday, inspection day, and the three people who had worked on Project Cactus most — Laurence, Hud, and I — finally installed the hood. This required adjusting a fender, drilling holes into the hood, and installing pins since the vehicle’s hood latch wasn’t working. In the end, this 1970 Chrysler Valiant finally had a full set of panels on it, likely for the first time in multiple decades:

I turned my 31 year-old back into a 51 year-old back by wiring up dash lights for multiple hours, and then I installed floor mats to hide any welding/grinding imperfections that the black paint couldn’t. They were the cheapest floor mats we could find; we glued them together to maximize coverage:

Then we installed the seat:

Between it, the floor mat, and those galvanized steel door panels, we actually had a decent interior!: d Hell, it’s more than decent if you compare it to where this vehicle started; what we have here is the interior glow-up of the century:

The final thing we did to prep Cactus for inspection was paint the bed floor, which was covered in welds and silicone. You can see Laurence wielding the spray gun in the screenshot below:

The bed went from this:

To this:

To this:

To this:

Convinced we’d made the most structurally compromised part of the ute both strong and aesthetically pleasing, and with new tires we’d had installed to the wheels, we hit the road:

Once on the highway, I got to see what it was like driving the ute at higher speeds — around 60 MPH. The alignment was clearly way off, as the car was a bit of a handful to keep straight, but everything else felt good — the ride, the engine, the transmission, the electrical system, the brakes. This ute didn’t feel like a rustbucket pretending to be a viable car; it was clear that the vehicle felt no imposter syndrome whatsoever — it felt deep in its core that it was a viable car.

The only surprise was that, once I got up to highway speeds, decades worth of rotten foliage and dirt shot out of the vents right into my face. It scared the shit out of me, but that second of fear was completely drowned out by joy. I was still worried that Project Cactus would fail inspection, and I’d then have only two and a half days to mend whatever was wrong, but I was just grateful to have come this far. No matter what happened at inspection, my trip to Australia had borne some incredible fruit, and I was never going to lose sight of that.

Laurence and I stopped by the car parts store to get a new license plate light, then dropped Project Cactus off at the inspector. From there, we could only pray. To keep our minds busy as we awaited the news from the car-doctor, Laurence took me to Dubbo’s foremost carburetor-tuner, an excellent classic-car mechanic named Timmy. His garage is full of some amazing stuff. There were rare cars:

More impressive than the cars was the hardware. Laurence showed me the innards of the legendary Hemi Six, particularly the big one — the 265 (Cactus’s is a 245):

Then he showed me the biggest mountain of carburetors I have ever seen: And a bunch of World War II military engines, including some radials and multiple V12 Merlins!:

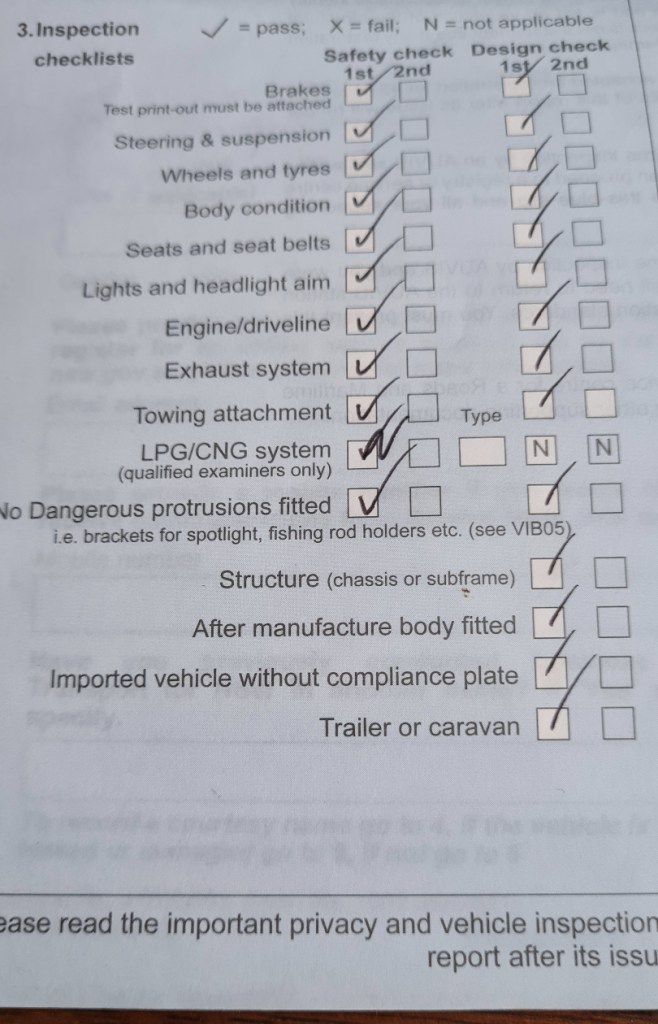

This incredible machinery kept my nerves at bay as I awaited the inspection results. After a few hours, Laurence got the call. “Your vehicle is ready for pickup,” the inspector said. “Ready for pickup?” I asked Laurence. “What does that mean?” “I dunno, mate. That’s all he said,” Laurence replied. We jumped into Laurence’s Chrysler Valiant ute, and, upon arrival, heard from the inspector that our exhaust was pretty damn janky, that one of the bolts in the steering system was too short, and that the hood pins weren’t technically legal. But then he handed this over:

The golden ticket! Project Cactus had passed inspection on its first try! I couldn’t believe it! Laurence and I — with help from some friends — had essentially built an entire car from scratch. All this time, all this agony, all of these repairs that each offered so many ways for us to screw up — somehow none of it had prevented us from passing New South Wales’ strict inspection. Elated, Laurence and I headed straight to the bar to celebrate:

He and I sat on that porch for hours. We were tired. Four weeks of nonstop wrenching had worn out our bodies and our spirits, and that moment — when we received that passed inspection notice — brought with it a humongous, almost overwhelming sigh of relief. I wanted to cry, but I was just too tired. Laurence and I just sat there, hung out, drank a beer, and talked about the Toyota Land Cruiser pig-hunting utes that drove by:

Before returning to Laurence’s house for the night, we walked around downtown Dubbo and just enjoyed the town, the people, and the history. It was a bit of tranquility between two storms — the unrelenting wrenchfest and the upcoming 400 mile roadtrip:

Just Before The Deni Ute Muster

. The following days were pretty chill. I proudly screwed the license plate on, then got the ute’s front wheels aligned at a local shop:

Laurence and I mounted that heavy ‘roo bar we’d bought out of a a field:

And I had a local business print out some decals that my coworker Jason had designed. You can see a few on the side in the image above, a little “A” on the front, and an Autopian sticker on the tailgate in the image below:

I ran by the local camping shop to pick up a “swag,” which is like a one-person tent (except better), and by Thursday — the first day of the Deni Ute Muster — Laurence and I were ready to hit the road — he in his ute, me in mine, and Bek in a Land Cruiser Prado.

Road-Tripping To The Deni Ute Muster

There was excitement in the air on Thursday morning; it was a huge day — hundreds of hours of work would finally be put to the test in the most fun way possible: a road-trip through the Australian bush. You have to realize that, at this point, I’d been in the country over a month, but I had barely seen any of it, as I’d been in the garage most of the time. I was just thrilled to know that, no matter what happens, at the very least I was going to be able to see some of Australia; a whole month there, with only a few glimpses of Sydney and the inside of Laurence’s shed would have been a humongous waste. Right out of the gate, my speedometer pretty much exploded in my dashboard. The noises it made as it screamed for mercy before its eventual demise were mechanical horror, but eventually I just unscrewed the thing from the back of the dash; by that time, my speedo was reading 60 MPH while the vehicle sat still. Oh well.

Laurence, a man about 1,000 times more organized than I, had planned our route a while prior, and though it wasn’t the most direct, it was absolutely stunning. In many ways, it reminded me of the American southwest, especially small towns like Tomingley, shown above; it has a population of just over 300 people, and is known primarily for its gold mine.

Laurence, Bek, and I then stopped by their friends’ sheep farm on what turned out to be one of the most beautiful afternoons I could have asked for. As far as I could gather, we were there, in part, to shoot the shit (i.e. “chinwag” or “gasbag” as Laurence’s mom Jan would put it) and in part to snag a sheep skull to decorate Project Cactus into its most “feral” state for the Ute Muster.

Laurence sells farm insurance all around New South Wales, so he spends lots of time road-tripping through rural parts of the state. As such, he knows where all the cool car stuff is, and he made sure to snake our route straight through it. Check out the field of classic cars above owned by a guy known as “Pink Eye.” I didn’t ask how he got that name, but I’m not sure I want to know.

In downtown Peak Hill, the same town where Pink Eye’s yard sits, is an old Holden dealership filled with low-mileage Holdens and car parts. An old General Motors Dealer sticker still adorns the glass window, with GMH — General Motors-Holden — reminding everyone of a time when Australia’s automotive industry was thriving. Chrysler and Ford were two big brands that built cars in Australia for Australia, but ask anyone who isn’t a diehard Ford Falcon fanatic, and they’ll tell you Holden was Australia’s car brand. It employed tens of thousands of people across the nation for decades, produced legendary cars that you’ll still find on posters on kids’ bedroom walls, and was fundamental to building car culture in Australia into what it is today. General Motors shut down its final Holden plant in 2017, and killed off the brand entirely at the end of 2020. It’s clear talking with Australian car fans how big of a pain this loss has been to them, and to Australia as a whole.

My eyes were agape as my right foot sent fuel to an Australia-engineered engine I had spent my first 30 years of life not knowing existed; the Hemi Six was divine — smooth, legitimately powerful, torquey down low, and paired beautifully with the relatively lightweight ute and the manual transmission.

All systems were functioning perfectly aside from that speedometer; Project Cactus was even scoring over 17 MPG and burning no oil whatsoever.

Laurence showed me another former Holden dealership that had been turned into an exhibit for the Elvis movie “Speedway” for an annual festival. As Laurence told me, a lot of small towns in rural parts of the country tried jumpstarting their economies by hosting movie-themed fests, or in this case an Elvis Festival. There was a Dolly Parton fest coming up, as well as a fest for the Australian automotive cult-classic “Running on Empty.”

From that town of Parkes, Laurence showed me “Bogan Gate,” largely because the term “Bogan” (the equivalent of “redneck”) perfectly suited Project Cactus:

I got to eat Barramundi, a delicious fish from which the most legendary Ford of Australia engine of all time gets its name: the mighty Barra.

We swung by the World War I memorial at Lake Cargelligo, where an older gentleman literally stopped his Mercedes in the middle of the road, got out, and talked Laurence and my ears off about our utes, and the old cars he “wish he hadn’t sold.”

One of the highlights of the trip to Deni was an art installation called “Utes On The Paddock.” Inspired by Texas’ Cadillac Ranch, it features some of Australia’s most historically significant utes, all donated from people around the country, and decorated in some kind of Australiana-theme by talented local artists.

In the background of the image above you can see one of my favorites, the Looute (basically, a ute turned into a porta-potty).

The Bundaberg Rum ute was amazing, highlighting a part of Australian culture that, I would later find, was pretty dang significant.

Look at that Emute. I love it!

The pastoral scene on the ute on the right in the photo above is awesome.

Get a load of this caption for the ute above, named “Circle work” after Australians’ term for ripping donuts:

Perhaps the most iconic of the art-cars in “Utes on the Paddock” were “Go Vegemite” and “UteZilla,” both shown above. And while those were obviously awesome, not just because they highlight two Australian cultural icons, but because they’re just so beautifully done, I want to highlight “Ute-opia”:

It’s an EJ Holden Ute with some palm trees sticking through it, and some animals below and on top; what’s most important about the piece is what’s written on the sign, for it perfectly describes Project Cactus when I first bought it:

The next few hours, cruising through wide open countryside, were among the most peaceful moments of my life. I watched as Australia got closer and closer in my windshield, and slid by in my side windows. Project Cactus dipped through deep water crossings from all the recent rain that had made my stay so cold and miserable the past month, and I ogled the beautiful wildlife.

If you look closely in this top photo, you’ll spot an Emu — a tall, hideous bird that Australia went to war with and, somehow, lost:

In this blurry photo, you can barely make out a kangaroo quickly hopping out of the street ahead of me:

As the sun began to set, Bek stopped to spend the next few days in Hay; Laurence and I set off for the final stretch — an hour and 20 minute straight-shot along the rural B75 highway. There was absolutely nothing out there except power lines, cattle, and kangaroos.

On this almost perfectly straight road — this home stretch — Laurence and I had some fun, shooting car-to-car footage, enjoying ourselves as you might imagine two buddies in their old Chrysler Valiant utes heading to a huge party would.

I’d sacrificed five weeks, an entire wardrobe, and probably a handful of years of life-expectancy, but finally, just half an hour ahead on this flat road was the payoff. My right arm rested atop the spindly steering wheel, my left arm rested atop the bench’s rear cushion, and I leaned back, listening only to the hum of that motor sitting at about 2,200 RPM. Wind whooshed in through my window as emotions flowed. I don’t know what happiness is — whether it’s a permanent state of mind or a temporary state impossible to pin down for long durations — but I can tell you this: Driving down that road in a ute my new friends and I had put our hearts and souls into; that was true hap— BAM! Project Cactus let out a loud explosion, its nose jerking hard to the right; my left hand quickly jumped to the steering wheel as my then-relaxed mind came into sharp focus, trying to move the wheel to get the ute under control. “Crap crap crap. We were there!” I thought, worried that the mechanical failure that my pessimistic mind had considered an inevitability had finally shown up for the party. I managed to steady Project Cactus’s heading, and pulled over to the side of the road. As I rushed to pop the hood, the problem became clear: I’d had a blowout:

And it wasn’t one of those “You ran over a rock” blowouts — no, this was a “Your entire tire is disintegrating”-type blowouts. Look at this!:

Apparently the torsion bars in our front suspension had “settled” since we’d gotten the alignment (or maybe installing that heavy ‘roo bar threw it off), as the toe and camber were now way out of spec. The vehicle drove reasonably straight on the highway, or at least so it seemed to me, but clearly the alignment had been way off.

The passenger’s side tire wasn’t in great shape, either, but it was good enough to get us another 20 miles to Deni; we decided to swap it with a rear tire, then install Laurence’s spare in place of the blown-out rubber.

The situation was far from ideal. For one, the sun had set rather quickly; this was a situation we’d been trying to avoid at all costs, as the threat of kangaroo collisions was very real at night, especially with our utes’ poor lighting. Second, Laurence feared he was running out of gas. And third, the only jack we had available was a steaming pile of crap.

Because the jack wouldn’t go high enough, I dug a small hole where the tire would sit, and while this wasn’t optimal, the jack’s biggest issue was that it leaked. So in order to get the spare tire on, Laurence had to fight the leak by rapidly pumping the jack as the vehicle wanted to lower itself, and I had to shove the wheel into the hole I had just dug, line up the lug studs, and shove. We got it done, and then headed back onto the final stretch, but within moments Laurence ran out of fuel, leaving me to go ahead into town. Seeing as Laurence’s ute was mechanically congruent to mine, I knew I was running on fumes, but that was the least of my worries; I was concerned about the kangaroos. Laurence and I had specifically chosen to leave early that day to avoid nighttime driving, but the blowout and now Laurence running out of fuel had put me into a tough spot. I was alone, driving in the middle of nowhere with barely any fuel and only weak candle-like headlights shining up potential bouncing mammals ahead.

This brings us to where this article started; I’m gripping my steering wheel hard as I look at huge bloodstains on the road and smell rotten kangaroo flesh through my vents. I’d been hearing about the dangers of kangaroo collisions for months, and I was nervously trying to scan the impossibly black horizon. Enormous stars did their best to aid me, but the reality is that only faith could guide me forward. I made it to the town of Deniliquin, filled up a jerry can, and rescued Laurence, who by then was sitting on his ute next to his open cooler, breathing down a can of beer.

The blowout and fuel issue had cost us too much time; the Deni Ute Muster was closed for the night, so we had to find another place to stay. After what felt like 1,000 failed attempts to find a camping spot, Laurence and I pointed our utes down a dirt road, parked the utes…somewhere, set up our swags in our beds, and basically died instantly.

We arose from our deaths under a big tree and a beautiful blue sky, and next to a frog-filled swamp and a bunch of lush green fields. Reinvigorated after a nice night of sleep, Laurence and I were high on life; two now-good friends driving in soulful, beautifully-running utes, just minutes away from a huge party — the excitement came through in every word we said that morning as we headed towards the fairgrounds:

On our way there, we had a local shop install a new set of tires, while Laurence and I checked out a car museum next door and took a ridiculous Back To The Future selfie:

With new rubber up front, we headed towards salvation.

The Deni Ute Muster

We drove through the gate, and snaked through fields of utes and campers as far as the eye could see. Though the Ute Muster’s PR team, who had kindly let us in for free, wanted us in a special media section, Laurence and I knew where we needed to go: to the Ute Paddock.

The Ute Paddock is the wildest part of the Muster, filled with Bundaberg Rum-drinking, whip-cracking, burnout-ripping Bogans of the highest order. Laurence knew we were in the right place when, immediately upon parking, Laurence had broken out some beers and dropped one on the ground. The beer can busted, spraying the brew everywhere. That’s when a random voice — perhaps from the ute gods who call these paddocks their home — yelled out “SKULL IT BUDDY!” I’d been at the Ute Muster for maybe sixty seconds, and I was already being forced to chug a beer. It was awesome.

Laurence and I fastened the Australian and American flag onto the bed, and tied our sheep-skull to the ‘roo bar. Then I drove through the paddocks.

That experience driving through the Deni Ute Muster’s paddocks was incredible. Look at the guy in the image above waving his arm; see the women sitting in the chairs below? They’re all yelling “Up it!” asking me to rev my motor.

As I drove through the campgrounds, dozens of people — men, women, old and young — yelled out “up it!” and “feed it!” and “Does she bang?!” Everyone was having an amazing time surrounded by fellow car-junkies.

I understand that this gasoline-fueled country ute fest isn’t necessarily a place where everyone would feel comfortable, and I’ll be the first to admit that “key banging” (which I’ll describe in a moment) is far from a sophisticated activity, but I can only tell you this experience from my vantage point, and I found the people to be warm, hilarious, and downright fun.

They brought some wacky utes:

They drank a lot of beer and Bundaberg Rum:

Like, a lot:

Folks were handing me all sorts of fluids; I grew quite fond of Bundy by the end of the night:

Folks taught me how to crack a whip! (I sucked):

They danced like there was no tomorrow:

They chanted “America: Fuck yea!” for reasons I have yet to surmise:

A gentleman named Sam gave me a tour of the Land Cruisers in the paddock; he’s incredibly well-versed in Land Cruisers:

They set their diesels’ exhausts on fire by covering the air intake with their hands, enriching the engine’s fuel mixture, shooting smoke from the exhaust — smoke that they then set on fire with a lighter. It was absolutely epic:

Perhaps the most exciting thing that I learned at the Deni Ute Muster was the concept of “Key Banging.” It involves revving your vehicle’s engine to redline, then quickly shutting off and turning on the ignition over and over; the idea is that the car will keep sending fuel to the engine even a few moments after the spark has been shut off. When the spark comes back on, the fuel mixture will be rich, and BOOM, you’ll get fire and pops from the tailpipe:

Folks key-banged all night, and I was told multiple people blew up their engines doing it.

As you can hear in the clip above, sleeping while folks were key-banging was not easy, but eventually the folks near Laurence and me took their keys out of their ignitions, and Laurence and I could rest in our swags.

As I sat there in my sleeping bag listening to faraway keg-banging, a country music concert, and fireworks popping off in the sky, I knew it was all over.

The clip you see above is that final moment of joyous relief. Five weeks; hundreds of hours of work; anxiety; fear; uncertainty — it had all paid off for this moment. Project Cactus had done it against all odds.

Saying Goodbye To Dubbo

The next morning, Laurence woke up early and donned his best modeling face (see above), then he and I packed our things and headed out:

It was just Saturday, and we’d only spent a single day — Friday — at the party. One of my favorite country musicians, Brad Paisley, was set to sing that tonight, and I had been excited to hear my anthem, “Mud On The Tires.” But I skipped out on Mr. Paisley, as I had somewhere more important to be.

Laurence and I met back up with Bek, and pointed our vehicles towards Dubbo, the town that had generously given me — a complete stranger— so many hours of its time to bring Project Cactus to life. This small agricultural and mining city, I had learned, was an automotive oasis in the middle of nowhere, and anyone who attended Cars and Coffee on Sunday could see that clear-as-day:

The love for cars runs deep in Dubbo, and in rural Australia at large. These people in the image below — Gordo, Ben, Mitch, Bek, Ross, Joanne, Hud, Callum, Henry, and of course Laurence — these people changed my life:

They changed my life almost as much as my final act did — my very last “drive” in Project Cactus. It was, of course, a shed-skid:

As I watched smoke billow out of Laurence’s newly-erected shed to join the sky that I’d soon be traveling through, I began to reflect upon that month in Australia. The whole point of Project Cactus had been to strengthen car culture — to bring an interesting, historically important car back on the road instead of allowing it to become scrap metal; to create fun content for people out there to read and watch so as to build their interest in cars; and above all, to bring car-lovers together for a common mission. But why should we even champion car culture in the first place? Why applaud something that clogs our streets with machines, fills our children’s lungs with noxious gases, segregates our communities with wide highways, destroys our ozone, and kills our loved ones? It’s a question I’d been asking myself for years, but one that I can now confidently answer. If the goal of our world is harmony — and I think it is — then there’s really only one way to get there: by collaborating with and listening to people from different backgrounds and with different creeds. This sounds simple enough, especially in a digital age that allows for communication through so many different methods, and yet, if the past few years have taught me anything it’s that even in a world of Reddit, Twitter, and TikTok, communities remain incredibly divided and misunderstood. We all live in our bubbles, watch the news channels that most align with our values, follow the Twitter accounts that confirm our beliefs, and avoid — perhaps intentionally or perhaps through our subconscious choices — people far outside our social and political spheres. This is a bigger problem for some than it is for others, but there’s little debate about how big of a deal it is for the country at large; we’re divided. And in a divided world, few things have more value than binding agents — interests or subcultures that can get people who are otherwise different to reach out their hand to another, and maybe crack open a cold can of Bundy. In my travels around the world in crappy old cars — in Turkey, in Bulgaria, in Serbia, in Germany, in Sweden, in Vietnam, in various parts of the U.S., in Hong Kong — I have made friends with people whom I might otherwise have had nothing in common with, and it’s all because of cars. There are other interests like sports and food and art that can accomplish a similar thing, but there’s no doubt that cars represent one of the strongest social binding-agents on earth, and despite the drawbacks of car culture, the value of such a binding agent should never be understated. Car culture is worth championing.

Here’s My Very First Look At The Two Dilapidated Chrysler Valiant Utes I Bought In Australia Why I’ve Decided To Fix My Parts Car Instead Of The Kangaroo-Hunting Ute I Flew 10,000 Miles To Australia For Here’s Why The Replacement Engine That Was Supposed To Save My $900 Australian Ute Is Nothing But A Paperweight What It’s Like Fixing Cars Infested With The World’s Biggest Spiders Plasma Cutters, Welders, Huge Spiders: My Hail Mary Attempt To Fix An Impossibly Broken $900 Ute In Australia Begins Here’s What I Learned At An Australian Cars And Coffee I Drove To The Middle Of Nowhere In Australia To Buy My $900 Ute An Engine That Was Buried In A Muddy Chicken Shed For Over 15 Years. Here’s How That Went Here’s How Screwed My $900 Ute Still Was After I Spent Four Weeks In Australia Wrenching Alongside A Hot-Rod Legend

Got a hot tip? Send it to us here. Or check out the stories on our homepage. Support our mission of championing car culture by becoming an Official Autopian Member. Long live The Autopian.